Visual Keystone Things learned creating the design of this site's remake.

I last touched this website three years ago. Back then, it was a single-page site with a custom Webpack setup, using Webpack like a static site generator through Nunjucks templating. Now I've remade, rewrote, and redesigned it with 11ty. There were several such attempts, all failing to gain traction. Among these, I lost the momentum of inspiration or had none at all, only knowing I wanted to make the site anew but without actual direction to do so.

The coding was easy. The writing and content were not, but this time I finished the redesign. This time was different because I realized something, a concept I'm calling the "visual keystone". After picking a single thing to base my visual design around, upon which to form other decisions, the rest came.

Design: The Eternal Enemy of Programmers

Finding things to write about myself and my projects is challenging. Finding relevant imagery is even harder.

For quite a while, I wanted a new developer site, at multiple points reattempting produce one I found appealing. Such a result hadn't come. Among these attempts, I started with a wants-driven approach. Knowing I wanted an 11ty site, knowing I wanted a portfolio within which to organize things I've worked on, knowing I wanted a place to put things I write, there seemed to be a starting point. But where does one go from there? Does one start with designing the site and composing words? Realistically, knowing requirements as simple as these does not indicate the next step.

In software, everything occurring is represented by the electrical happenings within semiconductors. Code does not lend itself to pictures. It would seem words are a better fit when discussing software, as programs are written in their own specialized languages. But although code is broken up into such words, they make for poor reading material. If one could convey their software by by displaying its code, expecting anyone to read it, there would be no need to write about software. This was at the core of my writers block. How does one design to present software development?

Using What I Have

When faced with an impasse in how to design a website for a software developer, the easy solution is to grab some photos of computer screens and coffee from Unsplash and call it a day. Perhaps a cyber-looking abstract picture. But barring the cliche and obvious, what image do you put next to information about a program or a developer?

My answer to this problem takes inspiration from O'Reilly and Manning books: anything. Here's a couple of their books, off my book shelf:

The O'Reilly book has an illustration of a different animal than the one in its name, and the chap in the Manning book probably hasn't heard of Amazon Web Services (I don't know, I haven't asked him), but these covers are great, notwithstanding my poor care for their physical condition.

Both software publishers have distinct styles for their covers; O'Reilly with its line-drawn animals, and Manning with their historical, painted fashion drawings. The selection of these distinctive, recognizable illustrations clearly identifies their catalogues. In other words, the answer to the question, "what image do you put next to information about a program" is "whatever looks nice."

As an aside, here's what O'Reilly and Manning have to say about their covers:

This takes it back to my website.

I've done Inktober a couple times. It's a drawing challenge where illustrators are provided a series of prompts to draw every day during the month of October. Full ink drawings can take 2-4 hours. It's grueling, but it made me a better illustrator through regimen, and provided me a starting point for subject matter to draw.

With all these drawings sitting doing nothing, I may as well use them to solve my problem! If a drawing tangentially relates to a subject I'm presenting, all the better, but relevance is unimportant. The realization it doesn't matter is liberating. It refocuses the design process from what I want onto what I have.

This site was redesigned several times before I realized this. Or at least, attempts were made. Once I decided to use my illustrations, once I decided on this one characteristic from which other design decisions would derive, everything else became easier. That was the most important thing: a central, visual keystone.

Making a light theme even though I'm a computer vampire and light themes burn

Choosing my ink illustrations as the imagery to appear throughout this site, I needed to determine how the other aspects of its theme looked. How would the illustrations and the site's graphics cohere?

My drawings have some common traits to build upon:

-

They tend to be high-contrast, pure black-and-white. Many use the negative white space to suggest the shape of objects.

-

Many of my drawings have frames drawn around them, but the subject of the image pops out of that frame.

-

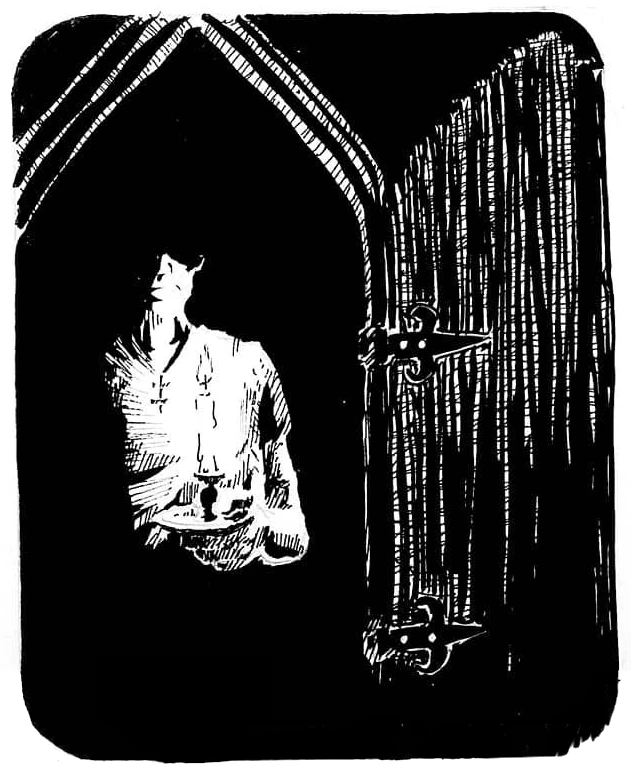

The use of implied line. This is where the outlines of shapes in a drawing are omitted, and instead are suggested by the shape of other lines and shadows. In the drawing at the top of this post, look at the candle for an example of implied line.

-

I like putting down a lot of ink. Fills are fun!

For these, a white background which matches the negative space of my drawings works best. They're drawn on white paper, after all, and I considered their value composition accordingly. Web pages are improved by contrast and variety in shape.

Visual diversity throughout the page provides users with a sense of direction. It gives them landmarks throughout the page, feeding their intuition. Juxtaposing curved lines with straight lines, big shapes with small, dark with grey with light, and other types of contrasts contributes to this variety.

Ink drawings can play into these qualities, these contrasts. If the drawing has a hand-drawn frame or boundary, that is one less use of straight lines. If the layout is the same in two parts of the site, two images differentiate them.

As for color, I'm breaking away from the inspiration I find in O'Reilly and Manning covers. A design choice which works well for them is pairing a bold, solid color with their illustrations. Solid bands of this color will feature prominently on the background of the book. If illustration is the primary trait of their designs, pairing them with a vivid, solid color is the secondary. Most of their illustrations will be in front of a white background, but this color will sit behind the background of its title.

When looking at my illustrations, however, that may not be the best match with my style. This is because of the large ink fills in my drawings, which would compete for value (darkness) distribution. In drawings with stark ink fills, introducing color can muddy the contrast. In fact, the way one inks an illustration may change depending on whether color will be added. Until I change my mind, I'm consciously sticking with a minimal palette: browser default colors for links, and the use grey lines as an accent.

An example of this is found in the "Other Projects" section in my front page. One of the projects I list, Flef, has a red logo. Currently, the other projects do not. Emblazoning the page in crimson vibrancy, it throws things off a bit. In order to maintain the balance of contrast at that part of the page, I reduce its opacity.

Similarly, the site uses grey lines, usually thin ones, as an

accent. I am partial to the color #8888, a 50% grey at 50%

opacity. Above almost any background, #8888 will always center

the color towards the same medium-grey. All-in-all, the intent of

these decisions is to give the site a "clear" look, while also

benefiting from the high contrast of the drawings. For this

reason, the site's appearance deviates little from the browser's

default theme.

Used deliberately, I suspect parts of the browser defaults may be an effective graphical design choice in websites. More and more, people spend their life using the same technology. You'd be hard-pressed to find an adult who hasn't used the internet for a decade. This gives web users a shared visual language. For example, if someone sees a circle with an X in it, they are likely to think it will close something. Most will see blue text with an underline as a clicky thing that takes them somewhere else. Web pages are variations upon the awful default CSS theme in browsers, which makes the default fundamental to a collective user conscious. Selectively maintaining parts of the default browser theme taps into the collective intuition of web users.

Even though I kind of hate light themes, that's why I'm going with one.

Ink CSS for a tentative dark theme

Even though this site has a light theme, even though there is no dark theme, even though a light theme is better for this website, I am a creature of the night and yearn for my website's embrace of the dark. Plus, if one day I add a dark-theme toggle button, then I get to be one of the cool kids.

Instead of creating a dark theme or a toggle button, I made my

<img> tags uselessly dark-theme friendly. Well, it's not that

useless, as some browsers support overriding the background color

of a page to enforce a dark theme. I defined a CSS rule for

elements with the .ink class, which sets black lines in the

image to to take on the inverse color of the background behind

them.

Under normal browsing conditions, because of the white background

you won't be able to see this <img> styling feature, but in

browsers which support it, the black pixels in images with the

.ink class invert the background behind them. For black ink on

a white background, this does not change the image. However, if

you change the background color, the image will pick a color to

so differentiate itself.

Here's an interactive demo to show this:

This demo is a web component defined in ./static/ink-demo.js

Here's the CSS for this ink theme.

@supports (

(filter: invert()) and

(mix-blend-mode: difference)

) {

img.ink {

filter: invert();

mix-blend-mode: difference;

}

}It's simple, but I think it's neat. Both filter and

mix-blend-mode are required for this to work, because the image

would appear inverted if only one of the CSS properties are

present. It essentially works by inverting the image twice. For

this reason, the style is wrapped in a @supports at-rule.

Additionally, my hope is naming the class "ink" aids the semantic

readability of the HTML markup by making it more descriptive of

the content; that an <img class="ink"> is an ink image.

Two-column layout with CSS grid hacks

With the illustrations being my website's chosen visual theme, and with a decision on colors made, what remains is the layout.

At the time of writing, this redesign has four pages: Home, About, Interbuilder, and Hefoki. The last two are project pages. Functionally, these are intended as overviews. On such pages, their design can be more presentational, more fancy. This is different from if the pages were are like the one you're reading now, a page comprising largely of text.

The visual keystone is the illustrations. For these pages, they can take up a large proportion of space. For this, I divide sections within the page into two columns, one with the picture, and one with the document content. As the user scrolls, sticky positioning makes the image follow the user.

On mobile, this doesn't work well. Both the text and image get too narrow for a phone screen, so a media query rearranges the layout. Instead of using sticky positioning within a grid layout on a narrow screen, the image appears below the heading using the default browser flow layout. From there the size of the image is bound to a maximum percentage of the screen height.

Here's a rough demo for this type of responsive layout:

This demo is a web component defined in ./static/demo-layout.js. Admittedly, I made it as an excuse to mess with container queries and have fun with CSS.

The HTML for this is dead-simple. The main CSS property set to

change the layout is the container's display property between

block and grid, and setting elements' grid-column property

when using the grid layout. Switching layouts this way maintains

a reasonable document flow and keeps the markup flat, like so:

Switching between a grid-based layout in desktop and to the browser's default flow positioning in mobile makes the markup flat, like so:

<section class="vertical-split">

<h1>Lorem Ipsum</h1>

<img class="slide" src="...">

<p>Amet ratione fugit at atque possimus?</p>

<h2>Ipsum incidunt!</h2>

<p>Elit ab saepe similique suscipit.</p>

</section>There's just one container, .vertical-split, and it's at the

top. For the image, one class, .slide is to be applied to a

direct descendant.

Here's an abridged version of the current CSS:

.vertical-split {

max-width: 1200px;

}

.vertical-split {

@media (

(min-width: 900px) or

((orientation: landscape) and (min-width: 750px))

){

display: grid;

--split-width: 350px;

grid-template-columns: var(--split-width) auto;

grid-column-gap: 2em;

@media (max-width: 1000px) {

grid-column-gap: 1em;

}

/*

By default, place items in the left column,

unless this has the .flip class

*/

& > :where(*) { grid-column: 1; }

& > .slide { grid-column: 2; }

& > .span { grid-row: 2 / span 9999; }

&.flip {

& > :where(*) { grid-column: 2; }

& > .slide { grid-column: 1; }

& > .span { grid-row: 1 / span 9999; }

}

& > .slide { grid-row: 1 / span 9999; }

& > picture.slide > :is(img, src),

& > img.slide {

position: sticky;

top: 0%;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

max-height: min(100%, 100vh);

max-height: min(100%, 100dvh);

}

}

}

.vertical-split > :where(img) {

margin: 0 auto;

width: auto;

max-height: 200px;

max-height: 50vh;

max-height: 50dvh;

object-fit: contain;

object-position: center;

}This does various things.

-

If any of the CSS features I'm using are unsupported, this should fail somewhat gracefully.

The most risky CSS feature used, at the time of this writing, is CSS selector nesting. When making static websites in the past, I've tended to use SCSS for this very feature, but today it's in CSS Baseline 2023 and has 91.53% browser support.

I've viewed this site with ancient, forbidden browsers. With the site being readable in IE5-6 and Safari from 2005, I think it's fine.

-

This component very easily adds variety to site the layout by horizontally swapping which columns have the image and text content. The

.flipclass will do this. -

A CSS variable to controls the size of the split. In HTML an inline style can change this value. This makes the design quick to change while maintaining responsiveness.

-

Pure CSS lets the browser do what it's good at, making the page faster.

Because this layout has classes and and variables which can tweak it, I've used it for all of the sections in the initial set of pages in the site. If I ever need to change the layout, because the HTML is flat, document-style HTML, it will unlikely need to be changed. And most importantly, it works for showing the images.

Inconclusion

My view on what constitutes a good design is subject to change, but this is where it's at now.

This article was more ambitious in its early drafts, but that was preventing me from finishing it. Ironically, there was a portion on accepting incompleteness in order to move things along, and holding onto that held back my progress. Similarly, I also wrote about splitting and distributing content across multiple pages, and I wound up doing that in this article, moving 1500 words into their own documents. Earlier drafts had sections on the site's written content and coding the static site generation. It's possible I talk more about these things in the future, but I figured it best to trim the scope of the article. Focus is a good thing.

Ultimately, if I were to distill my recent efforts into advice for other developers who need to perform some design work, figure out what you have. Perhaps you have some software you can compile into a web-based demo. Or if not, perhaps pick an arbitrary image theme, as I did. Maybe you're working with people who have visual assets. Whatever the case, take what you have and use that as your visual keystone. That demo needs a color scheme which frames it well. Images with texture can look good next to flat colors. Hopefully from there, the rest will come easily.